Gabrielle Émilie Le Tonnelier de Breteuil, Marquise du Châtelet-Laumont

© Thomas Wilson Shawcross 15 June 2005

Émilie du Châtelet (1706 – 1749)

I feel the full weight of the prejudice which so universally excludes us from the sciences; it is one of the contradictions in life that has always amazed me, seeing that the law allows us to determine the fate of great nations, but that there is no place where we are trained to think ... Let the reader ponder why, at no time in the course of so many centuries, a good tragedy, a good poem, a respected tale, a fine painting, a good book on physics has ever been produced by a woman. Why these creatures whose understanding appears in every way similar to that of men, seem to be stopped by some irresistible force, but until they do, women will have reason to protest against their education. ... I am convinced that many women are either unaware of their talents by reason of the fault in their education or that they bury them on account of prejudice for want of intellectual courage. My own experience confirms this. Chance made me acquainted with men of letters who extended the hand of friendship to me. ... I then began to believe that I was a being with a mind ...

from the Preface of Emilie’s English-to-French translation of Mandeville’s The Fable of the Bees

Emilie makes a good point here. As if further proof of discrimination against women were needed, Emilie, who translated into French the Principia of Isaac Newton and corrected his erroneous notation that energy equaled mass times velocity, is known primarily today (if at all) as merely the mistress of Voltaire! And, of course, her e = mc² equation is now associated with Albert Einstein, even though Emilie wrote it in the 18th century . . .

One has to wonder why it was that a young woman who could speak six languages and was capable of dividing nine-digit numbers by nine-digit numbers in her head had ever doubted that she was “a being with a mind.”

It might possibly have had something to do with the repressive attitudes of society in regard to the “proper” roles for women. As a woman, she was not supposed to be a scientist or a mathematician or hardly anything else that she was in real life (OK, her wife, mistress, and mother roles were acceptable, but that was about it).

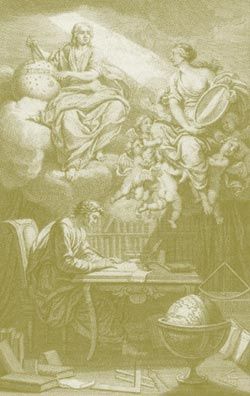

Jack Handey noted that “the face of a small child says it all, especially the mouth part.” Likewise, I think this illustration says it all for Emilie:

The frontispiece of Elémens de la Philosophie de Newton (1738) depicts Emilie du Châtelet as the goddess of truth, her mirror shining knowledge of the universe onto Voltaire as he transcribes the words of his female muse. Credit: Syndics of Cambridge University Library.

In truth, as Voltaire admitted to a friend, “She dictated and I wrote.” Voltaire put his name on their book, as it was unthinkable for a woman to have written it. Even the mirror reflecting the light from Newton onto Voltaire is held by a Muse goddess and not by a mortal female.

I often think of Emilie du Châtelet. She is an icon of what-might-have-been and symbolizes what society has lost through centuries of female suppression. Her life was a fascinating one, and I recommend further reading about her, but the purpose of this essay is not biographical. She has influenced my thinking, and so I am acknowledging that.

Her life accomplishments were extraordinary, but I find her death to be equally so. As a young wife, she had given birth to three children and thereby fulfilled her societal obligations. She and her husband decided not to live together (it had been an arranged marriage), and she took on Voltaire as her lover. They moved into her country estate and devoted themselves to intellectual and scientific pursuits.

At the age of 43, Emilie was dismayed to find herself pregnant by someone else (not Voltaire and not her husband). By the way, it is of interest to note that Voltaire helped her deceive her husband into thinking the baby was legitimate. Anyway, Emilie knew that a pregnancy at her age was the equivalent of a death sentence. One seldom hears about this anymore, but there used to be a common cause of death known as “childbirth fever.” This fever resulted from the infection that resulted after giving birth. Young women usually had strong enough immune systems to survive, but as they aged and their immune systems weakened, they often succumbed.

Emilie was determined that her translation of Newton’s Principia would be finished before she gave birth. Near the end of her pregnancy, she worked 18 hours a day on it, dipping her hands in ice-cold water to help stay awake. She finished the translation (including the correction of the energy/mass equation), gave birth to a daughter, and died of fever on 10 Sep 1749, several days after giving birth (par for childbirth fever). A trouper, Emilie had been working on the book when her daughter was suddenly born, and the babe was placed on a Quarto book of Geometry as Emilie was taken to her bed. Voltaire wrote to a friend, "It is not a mistress I have lost but half of myself, a soul for which my soul seems to have been made." Her book, Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy, was published ten years after her death.

TWS note: Newton's equation had been e = mv. Emilie's experiments showed it was e = mv², and Einstein took the velocity part and moved it to the highest velocity possible, i. e. "the speed of light" or "c"

Émilie du Châtelet (1706 – 1749)

I feel the full weight of the prejudice which so universally excludes us from the sciences; it is one of the contradictions in life that has always amazed me, seeing that the law allows us to determine the fate of great nations, but that there is no place where we are trained to think ... Let the reader ponder why, at no time in the course of so many centuries, a good tragedy, a good poem, a respected tale, a fine painting, a good book on physics has ever been produced by a woman. Why these creatures whose understanding appears in every way similar to that of men, seem to be stopped by some irresistible force, but until they do, women will have reason to protest against their education. ... I am convinced that many women are either unaware of their talents by reason of the fault in their education or that they bury them on account of prejudice for want of intellectual courage. My own experience confirms this. Chance made me acquainted with men of letters who extended the hand of friendship to me. ... I then began to believe that I was a being with a mind ...

from the Preface of Emilie’s English-to-French translation of Mandeville’s The Fable of the Bees

Emilie makes a good point here. As if further proof of discrimination against women were needed, Emilie, who translated into French the Principia of Isaac Newton and corrected his erroneous notation that energy equaled mass times velocity, is known primarily today (if at all) as merely the mistress of Voltaire! And, of course, her e = mc² equation is now associated with Albert Einstein, even though Emilie wrote it in the 18th century . . .

One has to wonder why it was that a young woman who could speak six languages and was capable of dividing nine-digit numbers by nine-digit numbers in her head had ever doubted that she was “a being with a mind.”

It might possibly have had something to do with the repressive attitudes of society in regard to the “proper” roles for women. As a woman, she was not supposed to be a scientist or a mathematician or hardly anything else that she was in real life (OK, her wife, mistress, and mother roles were acceptable, but that was about it).

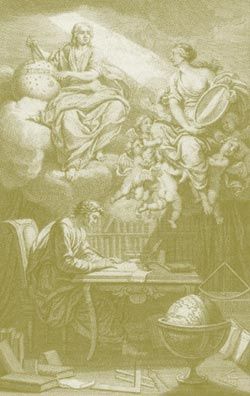

Jack Handey noted that “the face of a small child says it all, especially the mouth part.” Likewise, I think this illustration says it all for Emilie:

The frontispiece of Elémens de la Philosophie de Newton (1738) depicts Emilie du Châtelet as the goddess of truth, her mirror shining knowledge of the universe onto Voltaire as he transcribes the words of his female muse. Credit: Syndics of Cambridge University Library.

In truth, as Voltaire admitted to a friend, “She dictated and I wrote.” Voltaire put his name on their book, as it was unthinkable for a woman to have written it. Even the mirror reflecting the light from Newton onto Voltaire is held by a Muse goddess and not by a mortal female.

I often think of Emilie du Châtelet. She is an icon of what-might-have-been and symbolizes what society has lost through centuries of female suppression. Her life was a fascinating one, and I recommend further reading about her, but the purpose of this essay is not biographical. She has influenced my thinking, and so I am acknowledging that.

Her life accomplishments were extraordinary, but I find her death to be equally so. As a young wife, she had given birth to three children and thereby fulfilled her societal obligations. She and her husband decided not to live together (it had been an arranged marriage), and she took on Voltaire as her lover. They moved into her country estate and devoted themselves to intellectual and scientific pursuits.

At the age of 43, Emilie was dismayed to find herself pregnant by someone else (not Voltaire and not her husband). By the way, it is of interest to note that Voltaire helped her deceive her husband into thinking the baby was legitimate. Anyway, Emilie knew that a pregnancy at her age was the equivalent of a death sentence. One seldom hears about this anymore, but there used to be a common cause of death known as “childbirth fever.” This fever resulted from the infection that resulted after giving birth. Young women usually had strong enough immune systems to survive, but as they aged and their immune systems weakened, they often succumbed.

Emilie was determined that her translation of Newton’s Principia would be finished before she gave birth. Near the end of her pregnancy, she worked 18 hours a day on it, dipping her hands in ice-cold water to help stay awake. She finished the translation (including the correction of the energy/mass equation), gave birth to a daughter, and died of fever on 10 Sep 1749, several days after giving birth (par for childbirth fever). A trouper, Emilie had been working on the book when her daughter was suddenly born, and the babe was placed on a Quarto book of Geometry as Emilie was taken to her bed. Voltaire wrote to a friend, "It is not a mistress I have lost but half of myself, a soul for which my soul seems to have been made." Her book, Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy, was published ten years after her death.

TWS note: Newton's equation had been e = mv. Emilie's experiments showed it was e = mv², and Einstein took the velocity part and moved it to the highest velocity possible, i. e. "the speed of light" or "c"

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home