Nighthawks and Nighthogs

© Thomas Wilson Shawcross 20 Feb 2006

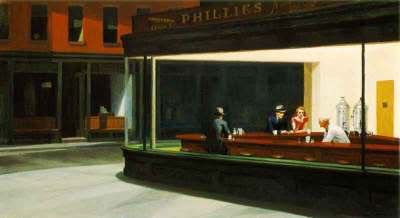

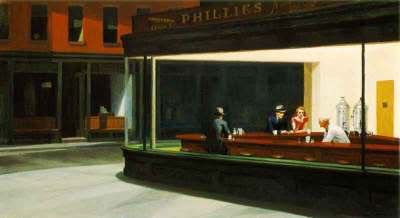

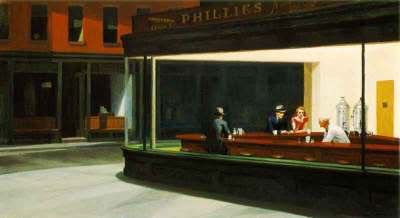

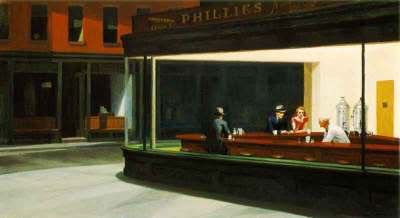

Nighthawks, 1942 Oil on Canvas 76.2 X 144 cm The Art Institute of Chicago

Edward Hopper’s paintings of urban scenes often convey a sense of calm, isolation, and detachment. His masterpiece painting Nighthawks has particular resonance for me, perhaps because my line of work has afforded me the opportunity to make solitary visits to late-night restaurants located around the globe. I feel as if I have been in this diner, and I suspect that is part of the wide appeal of this painting – many people can relate to this scene – and perhaps that is why Nighthawks is one of the most imitated, and parodied, of American paintings.

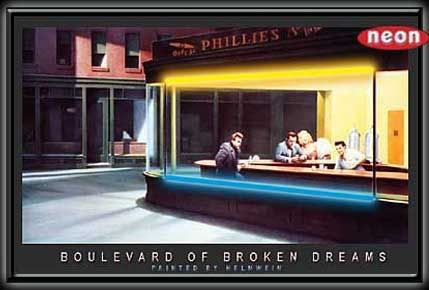

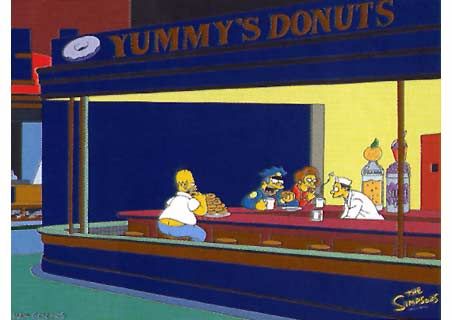

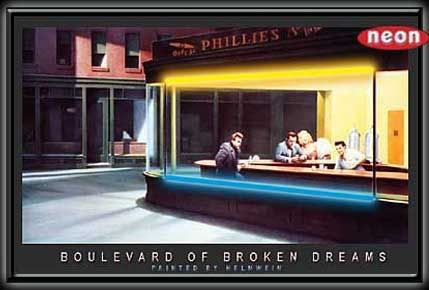

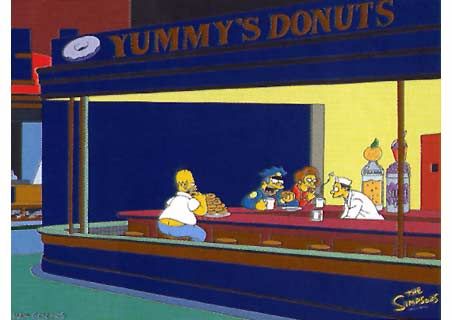

Until recently, I would have said that Nighthawks is one of the most famous American paintings, but a recent experience at work has caused me to re-evaluate my position on this. While sitting in on a code walkthrough, I noticed that one of the young developers had a Homer Simpson laptop screensaver that was a parody of Nighthawks. This was a new one for me. I had seen other parodies, the most memorable of which being Gottfried Heinwein’s Boulevard of Broken Dreams, in which the diners are replaced by figures of James Dean, Humphrey Bogart, and Marilyn Monroe – and the counterman is Elvis Presley.

Since two of the people participating in the walkthrough were from Chicago, where the original painting of Nighthawks is on permanent display, I figured they would enjoy seeing the newest parody of their “local” masterpiece. But, when I pointed out the Homer Simpson version to them, all I received in return were blank looks.

“See, this is a Simpsonized Nighthawks,” I offered. “Doesn’t this scene remind you of a more famous painting?” Nothing. Then, uneasy looks. Suddenly, the eyes of the developer brightened, and I realized he had caught on.

“Oh! You mean the painting with James Dean! And Elvis Presley!”

Boulevard of Broken Dreams by Gottfried Heinwein

That hurt. Suddenly, I felt very old. I recalled the time when I had told my Dad in 1963 about the “new” recording I had heard (Deep Purple by Nino Temple and April Stevens), and Dad had dryly informed me that Deep Purple had been a #1 hit in 1939. Now, I was my Dad. Well, that wouldn’t have bothered me, as he was a wonderful Dad, but now I felt as old as my Dad, and that did bother me. My colleagues in this walkthrough were all bright, young professionals – too young to remember the “Big Bang” (the original Nighthawks) that had launched a series of Art parodies.

A few days later, it occurred to me that perhaps this wasn’t an “age” thing, and maybe it was just a fluke. So, I conducted a scientific test and asked a cute girl at work (whom I thought had a pretty good head on her shoulders – but then, where else would it have been?) if she recognized the painting. “Sorry, Gramps, I have not seen it,” was her disconcerting response. Well, she did not actually call me Gramps, but that’s how I felt. So it was an age thing.

But, I digress. This story is supposed to be about Nighthawks and why Nighthawks has had such a powerful effect on (some) people.

Nighthogs (with apologies to Edward Hopper)

Many of the analyses of Nighthawks have concluded that it portrays urban life as empty or lonely, and they draw attention to the fact that scene shows no visible door. The conclusion is that the diners are trapped or confined (since there is no obvious way out).

I disagree. For one, if there is no way out, then how did they get in? Are we supposed to believe they are in some sort of human terrarium set up by space aliens for twisted space alien amusement? If so, then why don’t the male diners at least take off their hats? That’s the first thing I would do if I were trapped in a space alien terrarium. Well, maybe I would order some coffee first, and then take off my hat. Sometimes, one has to actually be in a situation before one can say how one would act.

No, I think the door was not shown simply so that Hopper could show more of the glass that surrounded the restaurant patrons, and thereby, more of the light that illuminated them.

Bear in mind that this painting was executed in January of 1942. As we all recall, fluorescent lighting was introduced in 1938. Think of the impact this would have had on a painter – someone who has been trained to see light professionally.

Edward Hopper was born in July 1882, so he was nearly 60 years old (still a young man, now that I think about it) when he saw fluorescent lighting in the actual restaurant that was the inspiration for this painting – a now-demolished restaurant near his home in Greenwich Village, New York City. The bright glare of fluorescent lighting offered possibilities for night scenes such as had never existed before. Although the objects in Hopper’s paintings often seem to be seen behind glass, Nighthawks is the only one of his paintings in which the glass is visible, a giant curved pane that allows a nearly unimpeded view of the Nighthawks inside.

Speaking of which, why isn’t this painting called Night Owls? Both owls and hawks are birds of prey, but people who like to stay up late are usually called Night Owls, not Nighthawks, so what does that tell us about what Hopper was thinking? Here is all that I have been able to find:

“Nighthawks seems to be the way I think of a night street. I didn’t see it as particularly lonely. I simplified the scene a great deal and made the restaurant bigger. Unconsciously, probably, I was painting the loneliness of a large city.”

EDWARD HOPPER

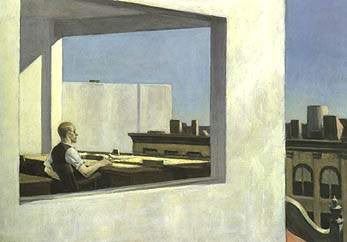

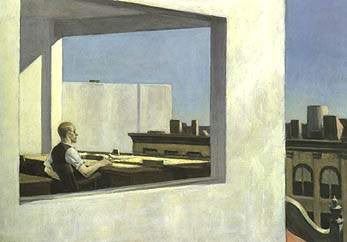

Edward Hopper’s paintings have been called “metaphors of silence.” Here is another example, a painting which for some reason always makes me think of Sioux City, Iowa (a 1998 work location of mine):

Office in a Small City, 1953 Edward Hopper

I think there is a temptation to over-analyze Hopper’s art and over-emphasize the lonely aspects: Text from "Sister Wendy's American Masterpieces":

"Apparently, there was a period when every college dormitory in the country had on its walls a poster of Hopper's Nighthawks; it had become an icon. It is easy to understand its appeal. This is not just an image of big-city loneliness, but of existential loneliness: the sense that we have (perhaps overwhelmingly in late adolescence) of being on our own in the human condition. When we look at that dark New York street, we would expect the fluorescent-lit cafe to be welcoming, but it is not. There is no way to enter it, no door. The extreme brightness means that the people inside are held, exposed and vulnerable. They hunch their shoulders defensively. Hopper did not actually observe them, because he used himself as a model for both the seated men, as if he perceived men in this situation as clones. He modeled the woman, as he did all of his female characters, on his wife Jo. He was a difficult man, and Jo was far more emotionally involved with him than he with her; one of her methods of keeping him with her was to insist that only she would be his model.”

As a student of Robert Henri, the founder of the Ashcan School of American Art, Hopper was taught to paint realistic scenes of urban life. Yet, unlike many of his fellow students, who focused on the more nitty-gritty aspects of urban life, Hopper looked at more common features motels, empty streets, offices, gas stations, etc., and he often was drawn to unusual lighting. Of himself, Hopper once said:

“Maybe I am not very human. What I wanted to do was to paint sunlight on the side of a house.”

Yet, there is an unmistakable human appeal to Nighthawks. The scene has inspired not only numerous parodies on canvas – also it has inspired writers to wonder about what dialogue might have been spoken by the people in the diner that evening.

I found two such stories using Google. My impression is that both stories had been written by young writers, as both stories referenced the restaurant as being a diner named “Phillies.” I assume these writers were not observant enough to spot the cigar icon and “only 5¢” to the left of the word “Phillies” and were too young to remember the advertisements for the popular five-cent Phillies cigar.

I doubt that the writers would have thought that the diner was named “Coca-Cola” if a Coke advertisement had been posted above the window.

Other writers have been content merely to reference Nighthawks, perhaps for its decidedly film noir connotations. Here is an excerpt from The Black Echo by Michael Connelly:

He made another one of those psychic connections with Eleanor Wish when he turned around and looked at the wall above the couch. Framed in black wood was a print of Edward Hopper's Nighthawks. Bosch didn't have the print at home but he was familiar with the painting and from time to time even thought about it when he was deep on a case or on a surveillance. He had seen the original in Chicago once and had stood in front of it studying it for nearly an hour. A quiet, shadowy man sits alone at the counter of a street-front diner. He looks across at another customer much like himself, but only the second man is with a woman. Somehow, Bosch identified with it, with that first man. I am the loner, he thought. I am the nighthawk. The print, with its stark dark hues and shadows, did not fit in this apartment, Bosch realized. Its darkness clashed with the pastels. Why did Eleanor have it? What did she see there?

Interestingly, according to the diary of his wife Jo, Hopper himself referred to Nighthawks as a painting “of three characters” (not four). Remember, he had used himself as the model for the two men at sitting at the counter, and his wife Jo was the model for the woman. So, in a sense, we see Hopper sitting at a counter across from himself and his wife.

Jo was often his female model, and she appears nude in several paintings, but in Nighthawks she is hardly the object of desire. One can infer from the placement of her hand near that of the man next to her that they are a couple, but they are each seemingly lost in their own thoughts (which do not seem to be about each other).

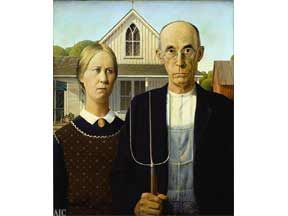

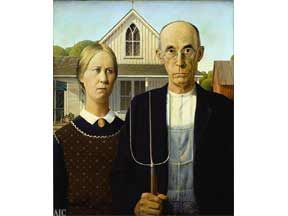

Perhaps the highest testament to the psychological impact of Nighthawks is the frequency in which it has been parodied. I think only one other American painting has been “covered” as often, and that painting is Grant Wood’s iconic Iowan farmer and unmarried daughter in American Gothic (which also resides in the Art Institute of Chicago).

American Gothic, 1930 Grant Wood

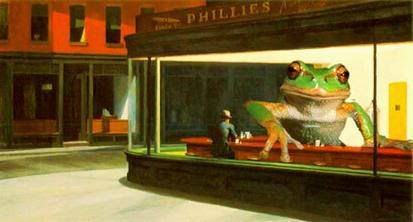

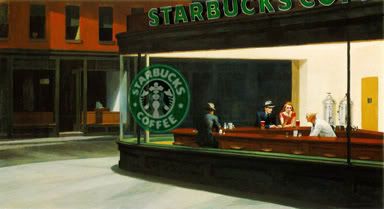

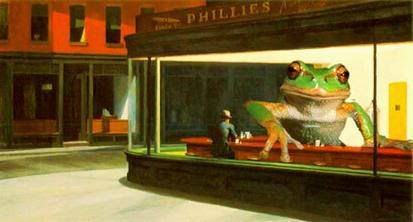

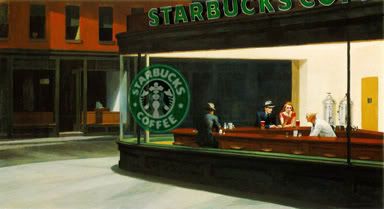

Here are some more of the many works inspired by Nighthawks. Which is your favorite?

Nighthawks, 1942 Oil on Canvas 76.2 X 144 cm The Art Institute of Chicago

Edward Hopper’s paintings of urban scenes often convey a sense of calm, isolation, and detachment. His masterpiece painting Nighthawks has particular resonance for me, perhaps because my line of work has afforded me the opportunity to make solitary visits to late-night restaurants located around the globe. I feel as if I have been in this diner, and I suspect that is part of the wide appeal of this painting – many people can relate to this scene – and perhaps that is why Nighthawks is one of the most imitated, and parodied, of American paintings.

Until recently, I would have said that Nighthawks is one of the most famous American paintings, but a recent experience at work has caused me to re-evaluate my position on this. While sitting in on a code walkthrough, I noticed that one of the young developers had a Homer Simpson laptop screensaver that was a parody of Nighthawks. This was a new one for me. I had seen other parodies, the most memorable of which being Gottfried Heinwein’s Boulevard of Broken Dreams, in which the diners are replaced by figures of James Dean, Humphrey Bogart, and Marilyn Monroe – and the counterman is Elvis Presley.

Since two of the people participating in the walkthrough were from Chicago, where the original painting of Nighthawks is on permanent display, I figured they would enjoy seeing the newest parody of their “local” masterpiece. But, when I pointed out the Homer Simpson version to them, all I received in return were blank looks.

“See, this is a Simpsonized Nighthawks,” I offered. “Doesn’t this scene remind you of a more famous painting?” Nothing. Then, uneasy looks. Suddenly, the eyes of the developer brightened, and I realized he had caught on.

“Oh! You mean the painting with James Dean! And Elvis Presley!”

Boulevard of Broken Dreams by Gottfried Heinwein

That hurt. Suddenly, I felt very old. I recalled the time when I had told my Dad in 1963 about the “new” recording I had heard (Deep Purple by Nino Temple and April Stevens), and Dad had dryly informed me that Deep Purple had been a #1 hit in 1939. Now, I was my Dad. Well, that wouldn’t have bothered me, as he was a wonderful Dad, but now I felt as old as my Dad, and that did bother me. My colleagues in this walkthrough were all bright, young professionals – too young to remember the “Big Bang” (the original Nighthawks) that had launched a series of Art parodies.

A few days later, it occurred to me that perhaps this wasn’t an “age” thing, and maybe it was just a fluke. So, I conducted a scientific test and asked a cute girl at work (whom I thought had a pretty good head on her shoulders – but then, where else would it have been?) if she recognized the painting. “Sorry, Gramps, I have not seen it,” was her disconcerting response. Well, she did not actually call me Gramps, but that’s how I felt. So it was an age thing.

But, I digress. This story is supposed to be about Nighthawks and why Nighthawks has had such a powerful effect on (some) people.

Nighthogs (with apologies to Edward Hopper)

Many of the analyses of Nighthawks have concluded that it portrays urban life as empty or lonely, and they draw attention to the fact that scene shows no visible door. The conclusion is that the diners are trapped or confined (since there is no obvious way out).

I disagree. For one, if there is no way out, then how did they get in? Are we supposed to believe they are in some sort of human terrarium set up by space aliens for twisted space alien amusement? If so, then why don’t the male diners at least take off their hats? That’s the first thing I would do if I were trapped in a space alien terrarium. Well, maybe I would order some coffee first, and then take off my hat. Sometimes, one has to actually be in a situation before one can say how one would act.

No, I think the door was not shown simply so that Hopper could show more of the glass that surrounded the restaurant patrons, and thereby, more of the light that illuminated them.

Bear in mind that this painting was executed in January of 1942. As we all recall, fluorescent lighting was introduced in 1938. Think of the impact this would have had on a painter – someone who has been trained to see light professionally.

Edward Hopper was born in July 1882, so he was nearly 60 years old (still a young man, now that I think about it) when he saw fluorescent lighting in the actual restaurant that was the inspiration for this painting – a now-demolished restaurant near his home in Greenwich Village, New York City. The bright glare of fluorescent lighting offered possibilities for night scenes such as had never existed before. Although the objects in Hopper’s paintings often seem to be seen behind glass, Nighthawks is the only one of his paintings in which the glass is visible, a giant curved pane that allows a nearly unimpeded view of the Nighthawks inside.

Speaking of which, why isn’t this painting called Night Owls? Both owls and hawks are birds of prey, but people who like to stay up late are usually called Night Owls, not Nighthawks, so what does that tell us about what Hopper was thinking? Here is all that I have been able to find:

“Nighthawks seems to be the way I think of a night street. I didn’t see it as particularly lonely. I simplified the scene a great deal and made the restaurant bigger. Unconsciously, probably, I was painting the loneliness of a large city.”

EDWARD HOPPER

Edward Hopper’s paintings have been called “metaphors of silence.” Here is another example, a painting which for some reason always makes me think of Sioux City, Iowa (a 1998 work location of mine):

Office in a Small City, 1953 Edward Hopper

I think there is a temptation to over-analyze Hopper’s art and over-emphasize the lonely aspects: Text from "Sister Wendy's American Masterpieces":

"Apparently, there was a period when every college dormitory in the country had on its walls a poster of Hopper's Nighthawks; it had become an icon. It is easy to understand its appeal. This is not just an image of big-city loneliness, but of existential loneliness: the sense that we have (perhaps overwhelmingly in late adolescence) of being on our own in the human condition. When we look at that dark New York street, we would expect the fluorescent-lit cafe to be welcoming, but it is not. There is no way to enter it, no door. The extreme brightness means that the people inside are held, exposed and vulnerable. They hunch their shoulders defensively. Hopper did not actually observe them, because he used himself as a model for both the seated men, as if he perceived men in this situation as clones. He modeled the woman, as he did all of his female characters, on his wife Jo. He was a difficult man, and Jo was far more emotionally involved with him than he with her; one of her methods of keeping him with her was to insist that only she would be his model.”

As a student of Robert Henri, the founder of the Ashcan School of American Art, Hopper was taught to paint realistic scenes of urban life. Yet, unlike many of his fellow students, who focused on the more nitty-gritty aspects of urban life, Hopper looked at more common features motels, empty streets, offices, gas stations, etc., and he often was drawn to unusual lighting. Of himself, Hopper once said:

“Maybe I am not very human. What I wanted to do was to paint sunlight on the side of a house.”

Yet, there is an unmistakable human appeal to Nighthawks. The scene has inspired not only numerous parodies on canvas – also it has inspired writers to wonder about what dialogue might have been spoken by the people in the diner that evening.

I found two such stories using Google. My impression is that both stories had been written by young writers, as both stories referenced the restaurant as being a diner named “Phillies.” I assume these writers were not observant enough to spot the cigar icon and “only 5¢” to the left of the word “Phillies” and were too young to remember the advertisements for the popular five-cent Phillies cigar.

I doubt that the writers would have thought that the diner was named “Coca-Cola” if a Coke advertisement had been posted above the window.

Other writers have been content merely to reference Nighthawks, perhaps for its decidedly film noir connotations. Here is an excerpt from The Black Echo by Michael Connelly:

He made another one of those psychic connections with Eleanor Wish when he turned around and looked at the wall above the couch. Framed in black wood was a print of Edward Hopper's Nighthawks. Bosch didn't have the print at home but he was familiar with the painting and from time to time even thought about it when he was deep on a case or on a surveillance. He had seen the original in Chicago once and had stood in front of it studying it for nearly an hour. A quiet, shadowy man sits alone at the counter of a street-front diner. He looks across at another customer much like himself, but only the second man is with a woman. Somehow, Bosch identified with it, with that first man. I am the loner, he thought. I am the nighthawk. The print, with its stark dark hues and shadows, did not fit in this apartment, Bosch realized. Its darkness clashed with the pastels. Why did Eleanor have it? What did she see there?

Interestingly, according to the diary of his wife Jo, Hopper himself referred to Nighthawks as a painting “of three characters” (not four). Remember, he had used himself as the model for the two men at sitting at the counter, and his wife Jo was the model for the woman. So, in a sense, we see Hopper sitting at a counter across from himself and his wife.

Jo was often his female model, and she appears nude in several paintings, but in Nighthawks she is hardly the object of desire. One can infer from the placement of her hand near that of the man next to her that they are a couple, but they are each seemingly lost in their own thoughts (which do not seem to be about each other).

Perhaps the highest testament to the psychological impact of Nighthawks is the frequency in which it has been parodied. I think only one other American painting has been “covered” as often, and that painting is Grant Wood’s iconic Iowan farmer and unmarried daughter in American Gothic (which also resides in the Art Institute of Chicago).

American Gothic, 1930 Grant Wood

Here are some more of the many works inspired by Nighthawks. Which is your favorite?

7 Comments:

Another excellent article, Tom.

You have a great sense for writing and if I were you, I'd pursue it.

And btw, who was the cute girl at work??!!

I liked the last one with the fish looking in. As usual, great writing!

I love the Starbucks Diner. That's really cute

I truly enjoyed reading this. I'll visit again.

hmmmm, an artist speaking here! what does this say about copyright infringements?

Edward Hopper was a great artist. I love his artwork. One day I'm gonna go to Chicago to see this fine art.

season1 ep8 of That 70s Show also shows a parody of this painting (which is why I looked it up online and found your article). In there it's also a restaurant named Phillies. I did like how they wrote it into the episode, despite the fact they overlooked the history behind the painting.

Post a Comment

<< Home